The Fifty-Minute Hour has sold millions of copies since its publication in 1955. The salacious marketing copy on the cover helped, undoubtedly!

When I was 15 I read “The Jet-Propelled Couch,” the true story of a psychiatric patient who believed he could teleport to a faraway planet. I’ve been fascinated ever since.

I learned about it from the Vaughn Bodē Index (1976). Bodē (1941-1978) was an underground cartoonist best known for Cheech Wizard. In an interview in the Index, Bodē lamented the fact that the patient in “The Jet-Propelled Couch” had been “cured” of his delusion. I was intrigued and wanted to learn more about this patient, so I scoured used bookstores in Boulder, Colorado until I found a copy of The Fifty-Minute Hour and Other True Psychoanalytic Tales (1955), by psychiatrist Robert M. Lindner (best known for his 1944 book Rebel Without A Cause: The Hypnoanalysis Of A Criminal Psychopath, which was the inspiration for the James Dean movie of the same name). The Fifty-Minute Hour contained five fascinating case stories of Lindner’s patients.

The most famous of the five cases was that of “Kirk Allen,” who Lindner described in the book’s final chapter, “The Jet-Propelled Couch.” According to Linder, Allen (a pseudonym) was one of Lindner’s patients, born in 1918, who was a physicist at “X Reservation,” a “government installation in the southwest” (probably Los Alamos National Laboratory). Allen had made important contributions during World War II (probably as part of the Manhattan Project). After Allen’s superiors observed him chronically spacing out on the job while muttering about his travels to other planets, they sent him to Lindner’s Baltimore office for long-term treatment.

Lindner described Allen as friendly and polite, and seemingly free of mental illness. But as Lindner got to know Allen, he learned that his patient had a traumatic childhood that affected him profoundly. Allen had grown up on an island in the tropical Pacific where he felt isolated from other children. His mother and father (a high-ranking member in the U.S. Military) paid little attention to him. “Throughout childhood and early adolescence,” wrote Lindner, “he was haunted by the difference between himself and his companions, a difference not solely of skin color but of social heritage and the innumerable subtleties of life.” To make matters worse, Allen’s governess sexually abused him for many months when he was eleven years old, which added further trauma.

While living on the island, Allen came across a series of science fiction/fantasy novels in the library that starred a protagonist who shared his name. The books provided an escape for his unhappy life. Allen read and re-read the novels.

“As I read about the adventures of Kirk Allen in these books,” Allen told Lindner, “the conviction began to grow on me that the stories were not only true to the very last detail, but that they were about me.”

He began fantasizing about additional adventures starring his namesake. His reveries were so rich in sensory detail that Allen came to the conclusion that his imagined escapades weren’t fiction — they were actually taking place in the future and he was somehow tapping into them. The fantasies grew and continued for years. He eventually discovered that he could leave his earthly body and travel forward in time to live as the heroic Kirk Allen on a faraway planet. He also learned he could spend a year or more as the spacefaring Allen and return to Earth, where only a few minutes had passed.

Here’s how he described the experience to Lindner:

One moment I was just a scientist on X Reservation bending over a drawing board in a clapboard B.Q. in the middle of an American desert—the next moment I was Kirk Allen, Lord of a planet in an interplanetary empire in a distant universe, garbed in the robes of his exalted office, rising from the carved desk he had been sitting at, walking toward a secret room in his palace, entering it, going over to a filing cabinet in a recess in the wall, extracting an envelope of photographs, leaving the room and retracing his steps, sitting again at his desk, and studying the pictures with intense concentration. It was over in a matter of minutes, and I was again at the drawing board—the self you see here. But I knew the experience was real; and to prove it I now had a vivid recollection of the photographs, could see them as clearly as if they were still in my hands, and had no trouble at all completing the map.

Allen was at a loss to explain how he was able to live in the past and the present simultaneously. “Have I discovered the secret of teleportation?” he asked Lindner. “Do I have some special psychic equipment? Some unique organ or what Charles Fort called a ‘wild talent?’ Damned if I know!”

Allen kept meticulous records of his future life. He gave his archives to Lindner, who was overwhelmed by their quantity and quality:

It is impossible to convey more than a bare impression of these. There were, to begin with, about 12,000 pages of typescript comprising the amended “biography” of Kirk Allen. This was divided into some 200 chapters and read like fiction. Appended to these pages were approximately 2,000 more of notes in Kirk’s handwriting, containing corrections necessitated by his more recent “researches,” and a huge bundle of scraps and jottings on envelopes, receipted bills, laundry slips.

There also were a glossary of names and terms that ran to more than 100 pages; 82 full-color maps carefully drawn to scale, 23 of planetary bodies in four projections, 31 of land masses on these planets, 14 labeled “Kirk Allen’s Expedition to —,” the remainder of cities on the various planets; 161 architectural sketches and elevations, all carefully scaled and annotated; 12 genealogical tables; an 18-page description of the galactic system in which Kirk Allen’s home planet was contained, with four astronomical charts, one for each of the seasons, and nine star-maps of the skies from observatories on other planets in the system; a 200-page history of the empire Kirk Allen ruled, with a three-page table of dates and names of battles or outstanding historical events; a series of 44 folders containing from 2 to 20 pages apiece, each dealing with some aspect — social, economic, or scientific — of the planet over which Kirk Allen ruled. Finally, there were 306 drawings of people, animals, plants, insects, weapons, utensils, machines, articles of clothing, vehicles, instruments, and furniture.

For over a year, Lindner tried to cure Allen of his delusion using every conventional method at his disposal. (He drew the line at electroshock therapy or a lobotomy, practices that Lindner abhorred). But after he’d run out of ideas and was at a loss for what to do next, Lindner says he had a “sudden flash of inspiration… in order to separate Kirk from his madness it was necessary for me to enter his fantasy and, from that position, to pry him loose from the psychosis.”

And so Linder began to act as if Allen’s futuristic fantasy life were real, and he dove in Allen’s archives with zeal. Anytime he found a discrepancy, he’d order Allen to use his “wild talent” to travel to his extraterrestrial palace library and perform a fact check. At first, Allen happily did as he was asked, but over time, his enthusiasm faltered. Lindner, on the other hand, became increasingly excited about his new role. As a self-admitted “rather reluctant addict” to science fiction with an “insatiable appetite for the stuff,” Lindner confessed that “I, the therapist, became quite involved in the psychosis of my patient and for a time and to some degree shared his obsession.”

But his obsession was short-lived. One day when Lindner was questioning Allen about some technical minutiae in the archives, Lindner noticed that Allen looked uncomfortable. When Lindner asked what the matter was, Allen said that a couple of months earlier he had come to the realization that he had been delusional all along, but had been faking it for the doctor’s sake.

“I realized I was crazy. I realized I’ve been deluding myself for years; that there never have been any ‘trips,’ that it was all just — just insanity.”

“Then why,” I asked, “why did you pretend? Why did you keep on telling me…?”

“Because I felt I had to,” he said. “Because I felt you wanted me to!”

Linder said that his temporary descent down the rabbit hole was a humbling and educational experience:

Until Kirk Allen came into my life I had never doubted my own stability. The aberrations of mind, so I had always thought, were for others. Tolerant, somewhat amused, indulgent, I held to the myth of my own mental impregnability. Superior in the knowledge that I, at least, was completely sane and could not — no matter what— be shaken from my sanity, I tended to regard the foibles of my fellows, their fears, their perplexities, with what I know now to have been contempt. I am shamed by this smugness. But now, as I listen from my chair behind the couch, I know better. I know that my chair and the couch are separated only by a thin line. I know that it is, after all, but a happier combination of accidents that determines, finally, who shall lie on that couch, and who shall sit behind it.

The Fifty-Minute Hour was a tremendous success, selling millions of copies over the decades, staying in print for over 60 years. (This is the only photo of Lindner I could find online. With his Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. mustache and combed-back hair, he looks like a matinee idol.) A Playhouse 90 production of “The Jet-Propelled Couch” aired in 1957 (starring Donald O'Connor, Peter Lorre, and Vampira) and composer Steven Sondheim started work on a two-act musical about Allen, writing three songs before abandoning the project.

When I read “The Jet-Propelled Couch” at 15, I was sure I knew who Kirk Allen really was. Lindner was duty-bound, of course, to not reveal the true name of his patient. He also presumably had to change certain details about Allen’s life history to throw sleuths off the trail.

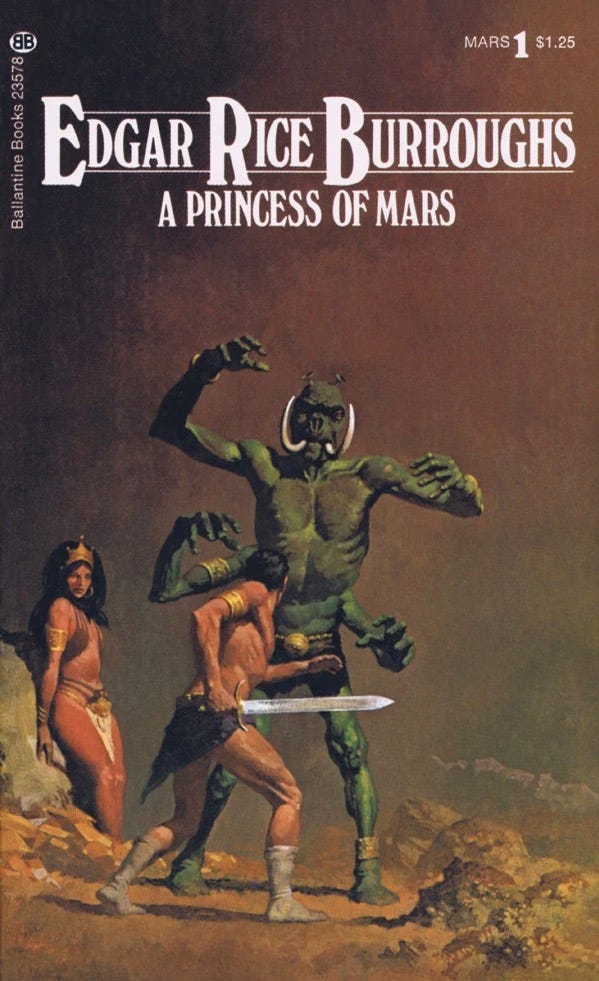

I read this Ballantine edition of A Princess of Mars, which I checked out from Nevin Platt Junior High School in Boulder, Colorado in 1973

But could there be any doubt that the novels that the young island-trapped Kirk Allen discovered were the John Carter of Mars series written by Edgar Rice Burroughs? I had read most of the John Carter books multiple times by the time I read “The Jet-Propelled Couch,” and it seemed obvious that Allen’s real name was John Carter.

The first novel in the series, A Princess of Mars (1912), offers a telling clue. When the novel begins, John Carter is being pursued by Apaches and hides in a cave. The cave harbors a poison vapor that paralyzes Carter. He struggles to get up, but can’t move. He tries even harder, and as Carter tells it, “something gave, there was a momentary feeling of nausea, a sharp click as of the snapping of a steel wire,” and Carter suddenly finds himself standing against the cave wall looking at his lifeless body lying on the cave floor. Carter’s astral body walks out of the cave where he sees Mars (as a “large red star close to the distant horizon”). He says:

My longing was beyond the power of opposition; I closed my eyes, stretched out my arms toward the god of my vocation and felt myself drawn with the suddenness of thought through the trackless immensity of space. There was an instant of extreme cold and utter darkness. I opened my eyes upon a strange and weird landscape. I knew that I was on Mars; not once did I question either my sanity or my wakefulness. I was not asleep, no need for pinching here; my inner consciousness told me as plainly that I was upon Mars as your conscious mind tells you that you are upon Earth. You do not question the fact; neither did I.

The description of Carter’s teleportation to Mars sounds a lot like Allen’s mode of travel through time and space. As a teenager in 1976, I didn’t know how to verify my hunch that Kirk Allen’s real name was John Carter, so I just had to satisfy myself with a strong suspicion.

It wasn’t until 40 years later that I learned that the answer was not so simple. I came across an article online titled “Behind the Jet-Propelled Couch: Cordwainer Smith & Kirk Allen,” by Alan C. Elms, which originally ran in the May 2002 issue of The New York Review of Science Fiction. It was written by Alan C. Elms,* a psychologist and biographer of science fiction writer Cordwainer Smith (pen name of a political scientist and psychological war expert named Paul M. A. Linebarger).

Elms spent many years trying to find out who Kirk Allen was, and traveled to interview people who knew Lindner in an attempt to get to the bottom of things. (Lindner, who died at 41 from a heart condition in 1956, a year after The Fifty-Minute Hour had been published, apparently took his secret to the grave.) Elms makes a convincing case that Kirk Allen was Linebarger, despite the fact that there is no known science fiction series from the 1930s or earlier featuring a protagonist named Paul Linebarger. (Elms confirmed that no scientist named John Carter worked at Los Alamos at the time.) Elms suspects Lindner changed many details to obscure Allen’s true identity and may have taken more creative license than he should have to make the story more interesting. But Elms’ research into Linebarger’s life story turned up enough similarities to Allen’s life to make a plausible argument that Allen was Linebarger:

Though I have yet to come across solid documentary evidence, I think the circumstantial evidence … is strong: Paul Linebarger was Kirk Allen, or at least a substantial component of Kirk Allen. It’s still possible that Robert Lindner combined two patients who suffered from apparently similar symptoms, better to conceal the identities of both and to make his main points about therapeutic technique more strongly.

I was initially disappointed that Kirk Allen wasn’t John Carter. But eventually, I decided it’s more fun that Kirk Allen will probably always remain a mystery.

The Fifty-Minute Hour is available as a “1 Hour Borrow” at The Internet Archive’s Open Library. That’s enough to read the “Jet-Propelled Couch” chapter.

Side note: Frank Frazetta painted the cover for the 1970 Doubleday edition of A Princess of Mars (left). He was afraid the publisher wouldn’t return the original art so he painted a second (and improved) version for himself (right). It sold at auction this month for $1.2 million.

*Interestingly, Elms was Stanley Milgram’s research assistant when he conducted his famous obedience to authority electric shock experiment. Elms wrote about it for CNN in a piece titled “My Summer with Stanley Milgram.”

The Magnet is written by Mark Frauenfelder and edited by Carla Sinclair.

I really enjoyed this.

What was the outcome of Lindner's patient?

My conceptualization of Lindner's case:

The key to this case is not "who" Kirk

Allen was, but that the patient knew he was faking--a real possibility that must be suspected whenever there is an alleged "psychosis". The patient couldn't keep up the pretense because, in fact, he was actually living in reality. He took pleasure in fooling others, which gave him a degree of personal autonomy that he felt he needed to conceal from others--especially because his work was top secret and was probably closely monitored. True psychosis would not "permit" transitioning from a world of sheer fantasy back to a world of reality that required extremely astute cognitions that are reality based.