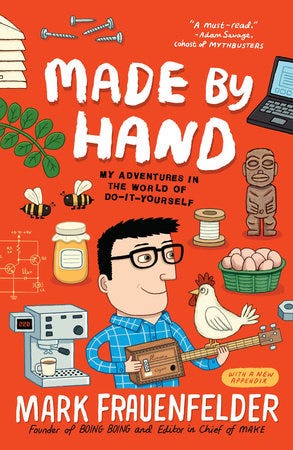

I wrote a book called Made by Hand, which came out in 2010. It was about my efforts to learn how to grow vegetables, make cigar box guitars, do science experiments with my kids, raise chickens, keep bees, whittle, and make furniture.

In the book, I told the stpry of getting to know my 80-something neigbor, Alfi, after a shaky start. This week, Alfi’s grandson told me that Alfi had passed away at the age of 97, “after a great long life.”

Alfi was a memorable and delightfully quirky man and I’m glad we became friends.

Here’s the chapter about Alfi.

One early December afternoon, while I was working in the guest house, I heard a loud car honk outside. I knew it wasn’t the UPS guy, because he announced his arrival with two polite taps on his truck horn. This honk was urgent and incessant. I hurried out of the cottage and saw a dust covered brown 1980s Crown Victoria in the driveway. When I got closer, I recognized the driver. It was Alfi.

Alfi’s a short, sturdy man who looks like Picasso. He’s about 80 years old. We were friends. We first met about four months ago, when I went outside one morning to pick figs from our fig tree. Alfi was at the tree, picking figs and putting them into a paper bag. He saw me, said hello, and kept picking. His audaciousness irked me. I curtly told him to save some of the figs for me, since I was the tree’s owner, after all. He retorted by saying “But they’re rotting!” When he looked at me, I saw that one of his eyes was bright blue; the other eye was milky white.

“I don’t care,” I said. “I don’t want you to take anymore.”

He grumbled and got into his car and drove off, taking several pounds of my figs with him. I picked the remaining ripe figs off the tree and brought them into the house. I had just started to tell Carla what had happened when we both heard an insistent series of honks outside. I looked out the window.

“That’s him!” I told Carla. “He came back!”

“Go out and see what he wants,” urged Carla.

I walked out and met him as he was getting out of his car. In his hands were a plastic bag and a small knife with an orange handle.

“I want to give you this,” he said, handing the bag to me. It was filled with garden-grown peppers, parsley, and basil. “And look at this,” he said. He leaned into the open window of his car, and grabbed a page from an Arabic newspaper. “Now, watch.” He held a corner of the sheet of newspaper in one hand and, with the orange-handled knife in his other hand, he began slicing strips from the newspaper, letting them fall to the ground.

“These are my knives. They can slice anything — except raw meat. Cooked meat OK, raw meat — don’t do it. My knives are in all the Subways. They all know me! Tell them you know Alfii. This knife is for you.” He held the knife out to me, handle side first.

Sheepishly, I took the knife, and introduced myself. I apologized for getting crabby with him about the figs. He explained that the previous owners of our house had given him permission to harvest figs and persimmons from the property, and he hadn’t realized they’d moved. I told him he was welcome to take our figs anytime, and he thanked me.

“Follow me,” he said. He got in his car and started driving away very slowly. I walked quickly behind the car to keep up. I wondered how long I was going to have to follow him, and where we going.

Alfi turned the corner and drove very slowly for another half a block, stopping in front of a vacant lot barricaded by a metal fence. He got out, unlocked the gate, and told me to walk in. The lot was about a half acre, and filled with black five-gallon plastic containers holding pepper bushes, citrus trees, and other vegetables. There were numerous other vegetables growing in the ground along with dozens of trees sagging with fruit.

“This was my house,” he said. “It was destroyed in the earthquake.” (He was referring to the Northridge earthquake of 1994, which killed 72 people, injured 9,000 people and caused $20 billion in damage.) Alfii’s house had been damaged beyond the point of repair, so he’d torn it down and turned it into a very large garden. He said he lived with his wife in a condominium a couple of miles away.

I wasn’t as interested in gardening then as I am now, so I didn’t pay a lot of attention to his garden, nor did I ask many uestions about his methods of producing such bumper crops.

But as the months passed, Alfi’s honks (and gifts of knives) became a welcome and almost regular occurrence. I started paying more attention to the tips he offered. He told me I should collect the fallen leaves and lawn clippings into a pile near my garden to make compost. He explained how I needed to prune away the branches from the fig tree once growing season was over to ensure a good harvest in the following year.

Usually, he offered this advice while helping himself to our persimmons, loquats, and feijoas, which he always took without first asking. By this time, I liked Alfi too much to care about this quirk of his. He never went into much detail about himself, but I learned he was from Iran, and besides being a knife salesman, he had also been in the book distribution business.

On this day, Alfi was with his wife, a pretty, well-dressed woman who looked to be ten or fifteen years his junior. “Do you remember me?” he said.

“Of course I do, Alfi!” I said, opening the gate to let him in.

“Good!” he said. “I’ve been trying to come here for persimmons, but you aren’t home.”

“I guess we just missed each other.” I told him that all the persimmons were already off the tree, but that I’d dried a bunch. I went in the house to get some for him. When I stepped back outside, Alfi was shaking the branches of the feijoa tree to make the fruits drop to the ground. He had about six of them in his hands, so I went back into the house again to get a bag for him, which he thanked me for. He filled the bag with fruit, went to his car, and gave me another knife, demonstrating its sharpness on a sheet of newspaper.

“Do you want to come with me now?” he asked? “I have things to give you.” I was interested to find out how his garden was coming along as it was early December. I hopped on my bicycle and pedaled behind his car.

After arriving in the yard, Alfi’s wife settled in one of the plastic lawn chairs under a large tree near the front of the lot.

Alfi got out of the car and said to me, “One day, I come over, I give your wife recipes. If you eat, you go crazy. You say ‘I live so long, I never tasted this food?’ Something out of this world. You’re going to thank me all your life.”

Alfi’s wife told me to bring my bike into the lot so no one would take it. “Good idea,” I said, bringing it into the yard and leaning it against a tree.

“Where did you learn to cook?” I asked Alfi.

“Oh, I know a lot of good recipes,” he said, leading me through the rain-soak grounds of his garden. “I know Israeli food, I know Iraqi food, I know Persian food. I know things you could not even imagine there is tasting food.”

Birds squawked at us from the trees. “Everything is mutual,” he said. “If you’re nice to me, I’m nice to you. I like you. The first time I met you I thought you were a good person.” (I wondered how he could think that, after I’d acted so peevish about his fig pilfering.)

He led me to the back of the lot. There were so many trees and tall plants around that I felt like I was in another country, not a mere block away from my house. A rooster crowed off in the distance. “I will show you something you can not even imagine.”

He stopped in front of a pepper plant loaded with chubby little green peppers. He picked one and handed it to me. “Eat this. It’s clean. Eat this pepper. It’s sweet.” I popped it into my mouth. He was right. It was sweet and crunchy. “It’s like cucumber,” he said.

“What kind of pepper is it? What’s it called?” I asked him.

He ignored my question. “I show you here,” he said. He picked up a one-gallon plastic container with a pepper bush, pulled a few of the brown leaves from it, and handed the pot to me. “Here. I give you this one.”

I thanked him and asked him again what kind of pepper it was.

“No no. This is different. You don’t find this in America.”

“Where did you get them?”

“From Middle East I get.” He started picking peppers from the larger bushes and handing them to me. I had no bag, so I stuffed them in my pockets. “They usually sweet at this stage, but be careful, because the weather is changing.”

I tried one. “They’re sweet,” I said.

“If you pick them small, they are sweet,” he said. “And I give you some recipes how you can use.” He started off in a new direction. I followed.

I noticed a rundown chicken coop along a fence near the back. “Did you keep chickens here?”

“I did keep, but a dog came and killed them,” he said. He stopped in front of a large pile of black compost, surrounded by ten or twelve five-gallon plastic pots full of the stuff in various stages of decomposition.

“This is the best compost in the world because this has worms.”

“Did you put worms in it?” I asked, looking at the pink and red earthworms wriggling in the soil he was upturning in one of the containers.

“They create worms!” he said. I asked him what he meant by “create worms.” He explained that crushed old fruit will actually spontaneously generate worms.

I had no desire to argue with him. I was more interested in finding out how he made this loamy compost.

“The scientists,” he continued, “they even don’t know how this worms eat the leaf and the shit that comes out of them — it’s the best fertilizer in the world. Oh my God, everything grow like you can’t even imagine.”

It was hard getting a straight answer out of Alfi, because he was always on to the next thing, walking away before I had a chance to fully understand something, but I told him I really wanted to know how he made the compost.

“I put leaves in a pile, and I put ammonium sulfate — you know ammonium sulfate? It looks like sugar. A bag 20 pounds for three dollars at Home Depot. Or horse manure. I mix, and put water and they will rot. They will be best fertilizer in the world. And something else — you know what is elephant garlic?”

“The giant garlic bulbs?” I asked, not sure what it has to do with compost.

“Yeah. I give you some babies, and if you grow them for thousands of years, without planting them every year you get some and they give babies and every year you will have them.”

I was trying to memorize Alfi’s compost recipe when he led me away. “I want you to try something else.” We wound our way through the dense foliage. We passed by a fig tree and I asked him about it.

“Oh, in March or February I give you cuttings. I have figs you’ve never tasted in your life. You don’t see them in the market. I have four or five kinds. I have some when you eat them — like chocolate. If you close your eyes and eat them, you think it’s chocolate.”

He stopped at a row of pepper plants and pulled a couple from each plant. Some were round like marbles, some were like small jalapenos, others were like cayennes. But they all tasted sweet. “You never get these peppers in America,” he said again. “If you chop this and you put one or two hot also with them and make an omelette with eggs — ah, delicious!”

Since we were on the subject of food preparation, I asked him if he made his own yogurt.

“It’s very easy. You know how?”

“No, I’ve been reading how to, but I don’t really know.”

“You boil the milk. It has to be whole milk. One or two boilings. Put it aside for a while until you can put finger in and it doesn’t burn. Then you put one or two or three spoons of yogurt and mix it and cover it and put it in the oven for a little while without the oven on and you wait a little while.”

Before I got the chance to ask him how long you have to wait, he had plucked a few small greenish yellow fruits from a nearby tree. They looked like unripe grapefruits. “These fruits you’ve never tasted in all your life.” He pulled a knife that was sticking blade down in a pot of dirt, rinsed it under a hose, and cut one of the lemons into quarters, handing it to me. I bit into it, expecting it to be tart, but it was just the opposite — sweet, like a kid’s drink, without acidity.

“This is sweet lemon,” he said.

“This is good,” I said. “will it grow from a seed?” I was thinking of saving the seeds from the piece he’d given me.

“No. No.”

“Is it something you got in the Middle East, too?”

“Yeah, yeah. And I’ll tell about this. If somebody has cold. If you eat eight, ten of this, he’s gonna jump back up after a day.”

My pockets full of peppers and sweet lemons, I said good-bye to Alfi and his wife and rode my bike home.

I hope you liked this snapshot of a remarkable person. I still use Alfi’s knives every day.

What a delightful homage to Alfii.