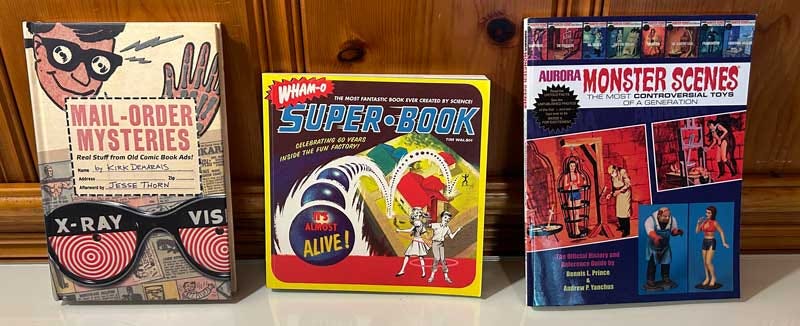

The Magnet 095: Mail Order Mysteries, Wham-O's Wonders, and Aurora's Torture Toys

Three books that reveal the weird and wonderful world of 1960s toys and novelties

Hi and welcome to another issue of The Magnet! I'm Mark Frauenfelder, and in this issue I'll be taking you on a nostalgic journey through three fascinating books that explore the quirky world of 1960s toys, novelties, and comic book ads. From mail-order disappointments to controversial model kits, these books offer a captivating look at the products that captured the imaginations (and allowances) of kids in a bygone era. Whether you're a collector, a cultural historian, or just someone who loves a good dose of vintage weirdness, I think you'll find plenty to enjoy here. Let's dive in!

If you're a paid subscriber, thank you for supporting my work! If you’re a free subscriber, thanks for reading! I hope you'll consider upgrading to a paid subscription. It's only $5 a month or $45 a year. Click the button below to find out more.

Aurora Monster Scenes: The Most Controversial Toys of a Generation

The first book is Aurora Monster Scenes: The Most Controversial Toys of the Generation, the Official History and Reference Guide by Dennis L. Prince and Andrew P. Yanchus.

In the early- to mid-1960s, the Aurora Model company produced a successful line of plastic model kits of famous classic movie monsters such as Frankenstein, The Werewolf, The Creature from the Black Lagoon, and The Mummy. In the 1970s the company started to branch out in a darker direction by introducing torture device model kits for kids. For instance, you could buy a Chamber of Horrors guillotine model kit for $0.98. It featured a man lying prone on a platform with his head sticking through the opening of a guillotine. The ad for the guillotine said:

"Harmless Fun! Flick a switch and the blade comes down… beheads victim… works over and over again."

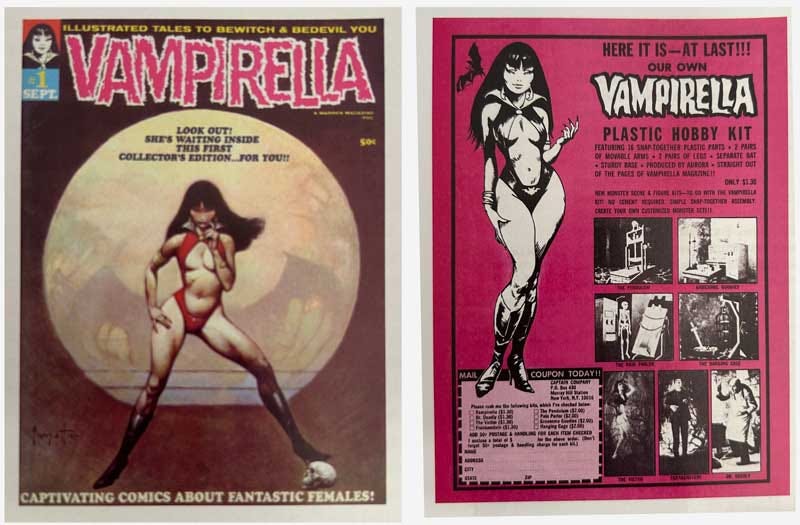

Soon after, Aurora licensed the usage of Vampirella, a character in a comic book published by Warren. She became the star of a new line of model kits called called Monster Scenes. Vampirella served as the muse and enabler of Dr. Deadly, a mad scientist who abducted innocent victims off the streets to torture and perform cruel experiments on. Dr. Strange's assistant was Frankenstein, who apprehended the victims and brought them to Dr. Deadly's torture chamber.

My introduction to these Aurora kits came from a ubiquitous comic book advertisement. The ad took the form of a single-page comic strip, featuring Dr. Deadly, Frankenstein, and Vampirella in the streets of New York City. In the opening panel, Dr. Deadly declares, "We need a girl victim for the experiment." Vampirella and Frankenstein eagerly comply. The next panel depicts Frankenstein forcibly seizing a young woman in shorts and a halter top, her cries for help falling on deaf ears. When Dr. Deadly commands to silence her, Vampirella reassures him, "Don't worry. This is New York. No one will help her." This chilling dialogue refers to the tragic case of Kitty Genovese, whose 1964 rape and murder became synonymous with urban apathy. The ad's casual reference to such a disturbing real-life event seems unthinkable by today's standards, but when I read it as a kid, it didn’t make a dent in my conscience. I was too busy trying to tell if Vampirella’s camel toe was real or an artifact of the poor printing quality of comics at that time. The remainder of the ad showcased the gruesome array of kits available for purchase: a swinging pendulum designed to bisect victims, an iron cage for imprisonment, and a brazier of hot coals for heating torture implements.

A newspaper article from the early '70s reported that over 800,000 Monster Scenes kits had been sold, noting:

"The list of grisly, sick scenes that can be staged with this equipment is, of course, limited only by your offspring's imagination. The chances are that a really disturbed kid could produce some stunners."

However, the tide of public opinion eventually turned. By December 1971, the controversy had reached such a fever pitch that government intervention became inevitable. A New York Times article dated December 20, 1971, announced:

"This will be the last Christmas that California youngsters can expect Santa to bring them a toy guillotine, a battlefield strewn with horribly wounded soldiers, or a doll that screams when she is tortured by a Frankenstein monster."

Governor Ronald Reagan responded by signing into law a bill that prohibited, effective July 1, 1972, the manufacture or sale in California of sadistic torture toys, toy bombs, and hand grenades.

Despite the backlash, some retailers were reluctant to give up on these lucrative items. A toy store manager in San Diego admitted, "I wouldn't buy one of them for my kids, but there's quite a demand for the kooky things. And if I don't stock them, someone else will."

The article went on to describe some of the best-selling items:

One of the best sellers among a score of torture toys is the doll that emits a scream when placed upon a thimble-sized torture rack by a monster in a blood-spattered white coat. The purchaser has the choice of three victims — man, woman, or child.

Another clerk in San Diego showed the reporter the “Pain Parlor” kit:

The basic kit, selling for $1.99, contained a brazier of hot coals with a branding iron and a rack for tearing plastic limbs away. Additional torture components cost $1.99, including a doll named Vampireilla, who comes with a plastic beaker of blood.

Aurora Monster Scenes covers the rise and fall of these toys in great detail and includes interviews, preliminary sketches, model sheets, and photos of assembled models. It's a fascinating bit of pop culture history.

Mail Order Mysteries: Real Stuff from Old Comic Book Ads

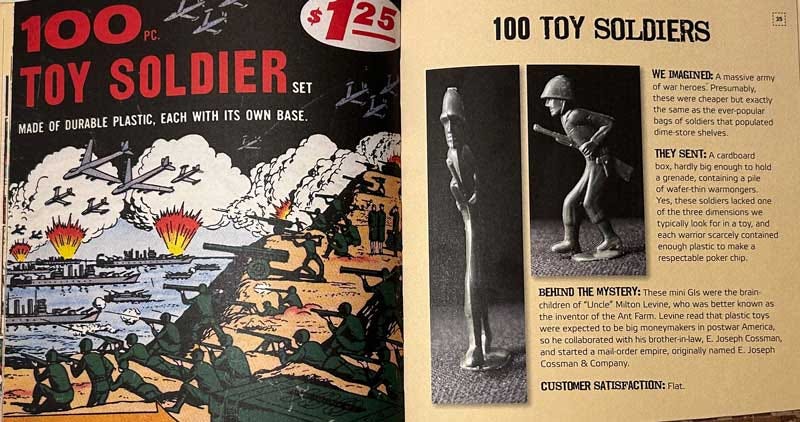

The second book is Mail Order Mysteries: Real Stuff from Old Comic Book Ads by Kirk Demarais. In the introduction, Kirk recounts being a first-grader buying a copy of Micronauts #9 in 1979. As he was paging through the comic, he realized that the advertisements were far more interesting than the comic book itself. He describes coming across a page of ads from the Johnson Smith Catalog::

"I turned to an overcrowded page of fascinating black-and-white drawings. I was captivated. It was an ink-smudged window into an unfamiliar realm where gorilla masks peacefully lived among hovercrafts and ventriloquist dummies."

Kirk explains the allure of these ads:

"To me, the ad's seductive nature was the result of a powerful combination of factors. Most obviously, the products were otherworldly: X-ray vision, karate courses, a money-counterfeiting device. They almost seemed too good to be true. For the first time, I wasn't thinking in terms of playthings. These were life enhancers that offered the means to satisfy a familiar range of wish fulfillment, including power, glory, revenge, and romance."

Kirk's parents forbade him from ordering these items, calling them "rip-offs." He later set out as an adult to collect them all on eBay, often paying 20 to 50 times the original price (“A small price to pay to uncover life's greatest secrets"). Kirk discovered his parents were right:

"Nearly everything is smaller, flimsier, simpler, or more inflatable than I imagined it to be. As a kid, I would have been devastated, but now the objects are symbols of a bigger story. As a consensual participant in the long-standing tradition of mail-order letdowns, I welcome the role of the rube and revel in the lackluster surprises that fill my mailbox."

The book juxtaposes the original comic book ads with photos of the actual items, revealing their true nature. It’s shocking to see how junky the items are. For instance, the “kryptonite rocks” were just plain old rocks coated in glow-in-the-dark green paint. The “U-Control Seven-Foot Life-Size Ghost” was a balloon with some fishing line and a trash bag.