Hi and welcome to The Magnet! I'm Mark Frauenfelder, and in this issue, I bring you a treasure trove of delights. Dive into the eerie and fantastical world of Weird Tales, explore a surprising culinary revelation with soft tofu, and ponder a fascinating, and controversial connection between Goya's art and Frankenstein's monster. As young Clint Howard said of tranya, “I hope you relish it as much as I.”

Free Unclassified Ads!

A couple of years ago, I started running Unclassified Ads in my Recomendo newsletter. The newsletter has over 80,000 subscribers. We charge $150 for an ad, and most people buy more ads after learning how well it does. I’m now running Unclassifieds in The Magnet, but with a twist: Subscribers get one free ad a year, and I’ll run them in the order I get them. The ads will be seen by paying and non-paying subscribers (12,100 as of today). Here’s the form to order an ad.

If you want to place an Unclassifed in The Magnet but don’t have a subscription, you can get one here.

Are you a senior executive who's frustrated by your team's performance? Join us at our complimentary monthly executive forums for great tips, tools and learning from fellow executives. Each month features a new focus topic and innovative ideas you can apply right away.

MEDIA

Download Digitized Copies of Weird Tales

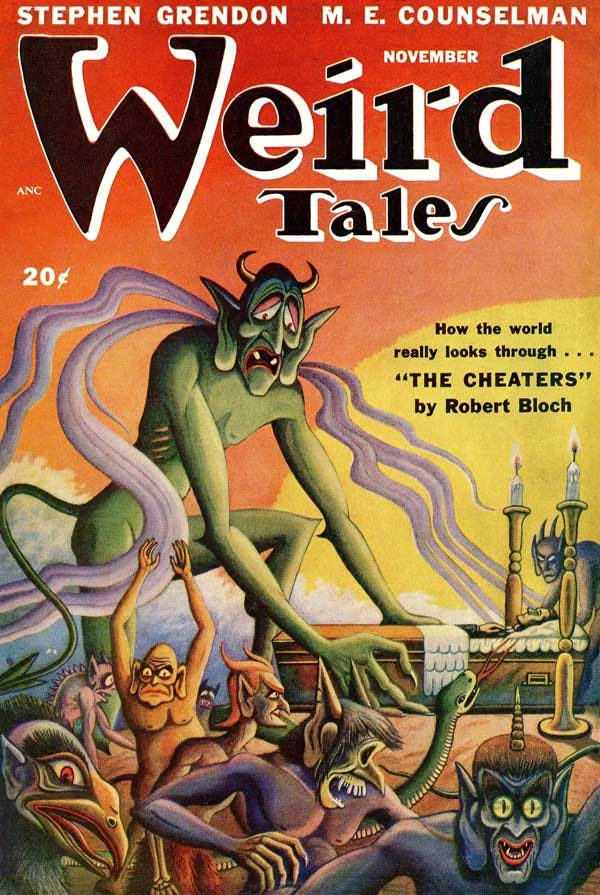

Weird Tales was a fantasy and horror magazine published from 1923-1954. Open Culture wrote of it — “As the Velvet Underground was to the rapid spread of various subgenera of rock in the seventies, so was Weird Tales to horror and fantasy fandom. Everyone who read it either started their own magazine or fanclub, or began writing their own ‘weird fiction.’”

Despite never achieving a large circulation, Weird Tales is famous for being the birthplace of H.P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu mythos stories. It also published Conan the Barbarian creator Robert E. Howard's first professional short stories.

My favorite thing about Weird Tales is the illustrations from its stable of fantastic artists. Here are the most notable:

Virgil Finlay - His detailed pen-and-ink style became a hallmark of the magazine from 1935 onward.

Margaret Brundage - Known for provocative covers, often featuring nude or scantily clad women in the 1930s.

Hannes Bok - Incredible surreal illustrations with psychedelic colors. I’ll bet the late underground cartoonist Richard Corben was influenced by Bok.

J. Allen St. John - He designed the title logo used from 1933 onward. Best known for his Tarzan covers. If you ever wondered who Frank Frazetta looked up to, here you go.

Boris Dolgov - Significant contributor in the 1940s and early 1950s, known for his distinctive style featuring thin, ethereal characters.

Lee Brown Coye - One of the five regular artists in the mid-1940s until 1954, known for his "Weirdisms" series of full-page illustrations.

Matt Fox - Painted eleven covers and contributed interior illustrations, including the image above. “He created ghouls, demons, and grotesqueries of all types, evoking a disquieting horror vibe that no one since has ever matched,” said Roger Hill, author of The Chillingly Weird Art of Matt Fox.

You can download digitized copies of Weird Tales at The Internet Archive.

(By the way, the Internet Archive is the greatest thing on the Internet. It has many lifetimes worth of old books, magazines, radio broadcasts, movies, ephemera and more. I donate to it every month. Please consider supporting it.)

ART

Look Familiar?

The Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California is not a large museum, but it’s a treasure trove of paintings, sculpture, and drawings. Its collection includes "Woman with a Book" by Pablo Picasso (1932), "Patience Escalier" by Vincent van Gogh (1888), "Madonna and Child with Book" by Raphael (1503), and "The Ragpicker" by Édouard Manet (c. 1865-1870). You can walk right up to the paintings with your nose an inch away, which I like to do to see how the paint was applied.

The museum also has wonderful temporary exhibitions. Last month Carla and I went to see I Saw It: Francisco de Goya, Printmaker, featuring Spanish artist Francisco Goya’s (1746-1828) darkly sardonic etchings from the late 1700s and early 1800s. Goya made these when he was deaf and isolated from the royalty who once courted him. The curator said of the work on display, “In witty, haunting and often raw narratives, Goya critiqued the abuse of power, both religious and political, his country’s prejudices and superstitions and the brutality of war.”

Everything in the exhibition was stunning, but I want to share one print in particular, “Los Chinchillas,” from 1799 (above). Does the figure on the lower left of the etching look familiar? He did to me. And when I read the signage next to the print, my suspicion was confirmed:

The Chinchillas’ title derives from a well-known play that Goya could have seen in Madrid's little theaters. It concerned the so-named family's excessive devotion to their distinguished ancestry as a tool to elevate themselves and avoid working. The artist's powerfully conceived figures had an interesting afterlife. The flat, square head and prominent brow ridge of the reclining figure at left inspired the makeup for actor Boris Karloff's role as Frankenstein in the 1931 movie.

William Poundstone writes about this on his LACMA on Fire website, and says if this claim is true, it would have helped the defense of people who had been sued for copying the Universal Picture version of Frankenstein’s monster (like Herman Munster and Franken Berry):

Intellectual property lawyers have split many a hair over Shelley's public domain novel and Universal's copyrighted interpretation of the monster's appearance. Visual adaptations of Frankenstein can be distinguished between those operating under Universal's license (the 1964-66 sitcom The Munsters) and those relying on fair use (FrankenBerry cereal), parody (Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein), Shelley's text (Mary Shelley's Frankenstein), and/or counterintuitively handsome monsters (Lisa Frankenstein).

A public domain source for the Universal Frankenstein in Goya could upset this applecart. But I suspect that [film historian Christopher] Frayling’s [unsubstantiated] claim [in his book, Mad, Bad, and Dangerous?: The Scientist and the Cinema (2005) and Frankenstein: The First Two Hundred Years (2017)] would fail to stand up in a court of law. In any case, the copyright for Universal's Frankenstein is set to expire in 2026.