The Magnet 047: What the co-founder of the Quantified Self has learned after 12 years of self-tracking

An interview with Gary Wolf on how to improve your physical and mental wellbeing without driving yourself nuts

My first encounter with Gary Wolf was in 1994 when he joined Wired magazine, where I worked as an editor. The sheer passion and curiosity with which Gary approached every topic astonished me. As a result, he is a fantastic journalist and editor, as well as a delightful conversationalist. It’s always exciting to talk to Gary.

For those of you not familiar with Gary’s work, I recommend these articles:

Twenty-six years ago, he wrote the fantastic article for Wired called “The Curse of Xanadu” that blew me away. The opening paragraph:

It was the most radical computer dream of the hacker era. Ted Nelson's Xanadu project was supposed to be the universal, democratic hypertext library that would help human life evolve into an entirely new form. Instead, it sucked Nelson and his intrepid band of true believers into what became the longest-running vaporware project in the history of computing — a 30-year saga of rabid prototyping and heart-slashing despair.

In 2008, Gary profiled Piotr Woźniak, a Polish researcher who developed a learning algorithm called SuperMemo widely used by language students. From the article:

SuperMemo is a program that keeps track of discrete bits of information you've learned and want to retain. For example, say you're studying Spanish. Your chance of recalling a given word when you need it declines over time according to a predictable pattern. SuperMemo tracks this so-called forgetting curve and reminds you to rehearse your knowledge when your chance of recalling it has dropped to, say, 90 percent. When you first learn a new vocabulary word, your chance of recalling it will drop quickly. But after SuperMemo reminds you of the word, the rate of forgetting levels out. The program tracks this new decline and waits longer to quiz you the next time.

It is evident from these two articles linked above that Gary is fascinated by how information is gathered, indexed, processed, communicated, and used. It’s not surprising that in the early 2000s, Gary was paying attention to a small group of people who were obsessively tracking things they could measure in their personal lives: what they ate, how much they slept, their heart rate, their blood pressure, their coffee consumption, their drug use, their anxiety levels, and so on.

In 2009, Gary and Kevin Kelly (another Wired veteran) founded The Quantified Self (a term they coined), and a nonprofit called Article 27 with the mission of “creating and using open tools to help everybody make meaningful discoveries with their own personal data.” (In 2010, Gary gave a 5-minute talk at TED@Cannes about self-tracking.)

Recently, Gary reached out to me about a one-button tracking device he is developing with some colleagues. I asked him if I could interview him for The Magnet about the device and what he’s learned from running The Quantified Self for 12 years and he kindly agreed. The following is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Mark: You’ve been doing Quantified Self for 12 years. What have you learned from doing it that long?

Gary: Well, it’s kind of obvious, but at the same time, it’s interesting that it’s not so obvious. Almost anybody can make a discovery using their own data and using their own capacity for empirical observation that will be meaningful in their life. It’s not something that requires an immense amount of training or expertise to do if you get a little bit of guidance and keep yourself from going down some path that will wipe you out. And so, seeing how powerful it is, and yet how universal it is — these techniques have been the key idea. It’s been the thing that has kept us going for a dozen years. And, there’s always something new that somebody is discovering that is amazing.

Mark: What are some of the most effective things you can measure in your own body?

Gary: Well, this is also a big lesson for us. The process of deciding what to measure is the most important process in quantified-self projects. And if you go wrong in measuring something that doesn’t work well, then all the rest of your work will be wasted. One of the ways you find out what is going to work for your own project is to avoid just taking measurements that are available to you and assuming they’re right.

So that’s a kind of “what not to do” bit of advice, but we live in a world where there are step counters, where there are heart rate monitors, where there are blood ketone sensors. All of this stuff comes into play and can be very useful, but the most important thing is to decide what phenomenon you want to focus on because it promises to answer your question.

And typically that phenomenon is something you can actively observe. Something that you can detect with your own consciousness.

I’ll give you an example of what I mean. A lot of people care about sleep. And there are lots of ways to measure sleep. And there are lots of devices and apps and programs.

But why do people care about sleep? For the most part, they care about sleep because they want to feel more rested. They want to feel more alert. The phenomenon they care most about is the feeling of being rested. It’s not, “Did the graph go up or down?”

Because if you start with just the sleep measurement device, and the graph is going up and down and all kinds of crazy ways, and you’re trying to make it go down, you start to have doubts about what it’s saying. You’re like, “Well, maybe it’s not even accurate,” or “Maybe it’s accurate most of the time, but on the nights it really matters, it’s not that accurate.”

And you can get really lost. And then you find people getting two devices or three or four, trying to figure out which one is best and calibrating it against the data they get in a sleep lab. This is where people drive themselves crazy. What we advise is, “Why don’t you start with what you care about?”

And if you care, for instance, about the feeling of being rested, start to make some observations of that feeling. Maybe it’s just once a day in the morning on a scale of one to five. “How rested do I feel this morning?” And do those observations for a good long period of time. Give it weeks, or even a couple of months of doing that every day.

It doesn’t take very much time. It takes 30 seconds. You will start to have a clearer and more focused picture of your goal and the phenomenon you care about most. And then, from that point, you can ask yourself, “What accounts for changes in how rested I feel?” And you can add things to measure that will help you explain why that core phenomenon has changed. And if you take that approach in the sense that you start with your own need, rather than what’s being offered to you as a measurement phenomenon, you’re going to end up learning a lot more, a lot faster.

Mark: That is fascinating. In the last year or so, probably because of the pandemic, I have gained a little bit of weight, and it’s noticeable because my clothes are too tight. What would you say would be the best way to get on a tracking program to make it so that my clothes fit better? I suspect it’s more than just weighing myself every day.

Gary: This is a great question. And we could talk for a minute, and probably I could help you a little bit. But of course, we can talk again in two months or six months. But one of the questions about gaining weight is, why do you think you gained weight? Because there are different reasons that people gain weight. So if you want to start to operate on this system of weight gain and weight loss, it’s good to start with what you already know. Do you already know why you gained weight?

Mark: I do know exactly why, and it’s because I just kind of gave up on restricting my carb intake. And so I was eating lots of bread, lots of cake, pancakes, that kind of stuff. And that makes me gain weight.

Gary: So, if you were to try to stop eating all those carbs, you probably have, like I have, and everybody has.

Mark: I’ve been pretty hardcore keto for the last two weeks.

Gary: Two weeks. Okay. And are you losing weight yet?

Mark: I am. I’ve kind of hit a plateau, but I quickly lost probably, seven or eight pounds in a week. And now it’s just hovering around the same amount. I’m still heavier than I want to be. I weigh myself every day on a Withings scale. I’m considering getting a ketones blood test kit on Amazon. They look like they’re pretty inexpensive. But people say that those numbers are all over the place all the time. And so it’s hard to like get a reliable reading.

Gary: So let’s talk for a minute about ketone measurement, and then we’ll go back to the larger question. We’ve seen some incredibly great talks about measuring ketones to accomplish different kinds of goals. It’s not always weight loss, but it can be weight loss. And I think it’s amazing that that kind of measurement is available. And the place I’ve seen it work best and provide the most meaningful discoveries is to people who are settled into a ketogenic diet regimen. They solved many of the problems of daily life that people face when trying to get themselves into a regimen like that.

It fits their lifestyle. It’s okay with their family. They have foods that they like to eat. They don’t get side effects. They’re kind of in a groove with keeping themselves within that regimen, but they’re wondering about really specific foods. Like they’re wondering, “What kind of wine can I drink and still stay in ketosis?” or “I’m eating some carbs every day, not a lot. What is my upper limit?” or “What is my upper limit within a specific period of time?” So here you have really refined questions, which could not be answered without this instrumentation.

And once you do answer them, it can be great for you. We had a talk given by somebody testing these completely fermented sugar-free wines, which had alcohol in them but were not driving his carb metabolism. And so he could drink that, which is great for him. But you don’t know for sure that this is the right regimen for you over months and years. You’re only two weeks in. So probably for you, it’s a bit of a waste of time to start right into that. Probably for you, you’re still trying to find like, “What is the barrier that either keeps me in or keeps me out of... like for instance, do you ever cheat?”

Mark: I just had sushi for lunch. So there was rice involved, but that was it.

Gary: So you’re in that golden phase.

Mark: Yeah, exactly. And I’ve done pretty well. I’m a good cook. I’ve figured out ways to make things I like that taste really good and are almost carb-free. So I don’t think I’ll have a problem enjoying what I eat. I just can’t get back into that groove of the cake and wheat and all that kind of stuff.

Gary: Right. What effect is it having on you overall? Is it all positive effects, or are there any negative effects

Mark: So far, no negative effects. It feels good. And I should say that about ten years ago, I did an Atkins-style diet. When my weight crept up, it did help a lot. I dropped weight like crazy when I did that. So I do think that a low-carb approach is right. I’m not sure that keto itself is the right way, but I thought it was such an extreme low-carb diet that it might be something worth trying.

Gary: For sure. So this is great then, Mark. What I would tell you is, do not waste your empirical energy at this moment loading on research questions just because you could. Everybody’s life produces these kinds of big question marks where you’re like, “Okay, now I have to think about this because something’s gone wrong.” But you don’t want more of those than you have to have. So my nonclinical quantified-self advice to you would be to do nothing for the moment. Continue what you’re doing. And wait until you get one of these big question marks, and then that’s when to apply the sort of medicine of empirical research on yourself.

Mark: Not even weighing myself?

Gary: We’ve seen great plots where people weigh themselves, like once a week or once a month. Because if your goal is to lose weight steadily and get to some ideal weight, you don’t need to know what you weigh every day.

Mark: In fact, you were the one who told me a few years ago the best way to weigh yourself is with a scale that displays only your 10-day rolling average.

Gary: That was the second instrument we wished we could make. In the utopia of open hardware, we would have a programmable scale where you could just lock the display because we’ve seen a lot of talks where people have found a way not to be confused by the quite significant variation in daily weight. And some people start by weighing themselves multiple times a day, which to me is crazy.

Mark: I think that’s just the excitement of starting a new thing.

Gary, I know you have to go, but just in the next couple of minutes, could you tell me about the one-button tracker that you have been working on?

Gary: There’s nothing I would rather tell you about. One of our biggest discoveries has been how important active tracking is for helping people focus on the phenomenon that really matters to them. And so we make a distinction between foreground and background observations, in which the foreground observations are these kinds of highly relevant phenomenon that you care a lot about. And the background observations are the things that help you explain the variation in the foreground observations.

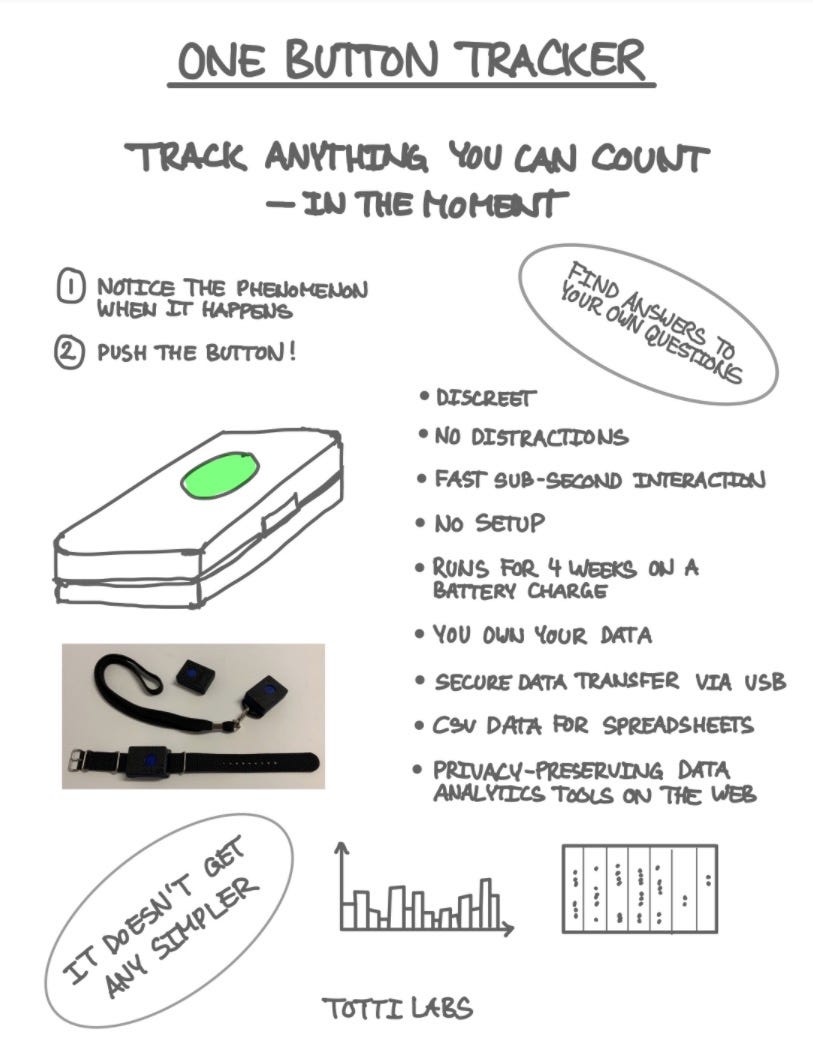

The problem has been that you actually need a little bit of help collecting these foreground observations. For instance, I have a really detectable cardiac arrhythmia, and I want to know when I get it. I notice it, but I don’t want to pull out my phone every time I feel it. I might be in a conversation or at a meal or something and open an app and record that I feel it. So, we have finally in our hands an open hardware project, and it just has a single button on it. And when you press the button, it records the time of a self-observation. And that record — the series of times you’ve pressed the button— is just available as a CSV [spreadsheet] file on the device. So we feel like we solved the problem for people who are making active observations. It doesn’t have any other solution.

Now there is a problem with the device: each one is made by hand by Thomas Christiansen and Jakob Eg Larsen at Totti Labs. They’re the inventors, and they’re also the manufacturers to the extent that they’re manufactured. They 3D print the cases, and there’s a little chip inside and some other things needed to make the button work, but hopefully, by next year, they’ll be available to people to make at home or in a kit form.

Mark: That sounds so cool. For example, sometimes I get a hallucinatory smell of smoke that comes from nowhere. No one else can smell smoke, but I can. And it lasts for a couple of days. It happens every few weeks and can persist from one day to a few days. Having something like this, I could just press the button every time the smell hits me. I could look and see patterns. Like, “Does it happen when I come back from a trip?” or “Does it happen when I use my laser cutter that produces smoke?” It seems like a useful thing for something like that.

Gary: It’s perfect for that. And that’s also a great illustration of this distinction between foreground and background phenomenon. So the smell of smoke is the foreground phenomenon. That’s the thing we care most about. But there’s a lot of location trackers out there. You could run a passive location tracker on your phone and we would call this the background data. And you can just let that run in the background. You’re not doing anything. And then later, when you look at the time in which you had that hallucination of smoke smell, you could then just refer to your background data and ask, “Well, where was I at that moment?” And maybe you would see something, you know, and then maybe you could run a really simple experiment, like, “I’m going to do that activity every day for a couple of weeks. And I’m going to see if my incidents of smelling smoke go up or don’t.”

Mark: Gary, I’m going to let you go cause I know you have to take your friend to the airport, but this has been super interesting and helpful just for me personally.

Gary: You know, Mark, if you want, let’s talk again in a few months. Let me give you any kind of help that I can.

If you enjoyed this issue, please consider subscribing by clicking this button: