The Magnet 0015 — How to talk to people 10,000 years in the future

Your challenge: warn those in the far future to stay away from deadly nuclear waste dumps we left behind

The world has generated an awful lot of radioactive waste since the first nuclear test blast took place in 1945. The problem is, it will still be a problem after our generation is gone—loong gone.

Nuclear waste is so nasty, and there’s so much of it, that it’s ironically become a money-making “anti-commodity” on the world market. Governments pay nuclear waste and repository companies billions of dollars to take it off their hands.

The U.S. currently has 80 sites to store its radioactive waste, but only one is designated a “deep geologic long-lived radioactive waste repository” designed to quasi-permanently entomb spent nuclear reactor fuel rods and other detritus of the atomic age. It’s called the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) and is located 26 miles from Carlsbad, New Mexico. WIPP currently holds 2 million cubic feet of radioactive waste, buried a half-mile deep in a natural salt deposit. The plan is to keep filling the hole until 2070, then seal it. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has mandated that the waste destined for WIPP be kept safe from the possibility of exposure for 10,000 years.

Ten thousand years is a long time, but it’s not long enough, because the kind of radioactive material being stored there will remain extremely lethal for at least 100,000 years. The EPA’s plan is akin to sending a scuba diver on an hour-long mission with six minutes of air in their tank.

But ignore for a moment this literally fatal flaw and consider the enormity of the task at hand — how do you warn people from 10,000 years in the future to steer clear of this deadly dump? After all, Stonehenge is only about 3,500 years old and experts can’t figure out whether it’s a big sundial or a monument to the vagina. Even now, most English speakers have difficulty comprehending Shakespeare without assistance. Whatever languages people from the year 12,000 will be speaking, they won’t be anything like the ones spoken today.

With that challenge in mind, in 1991, the Department of Energy commissioned an anthropologist, an architect, a materials scientist, an astronomer, a linguist, and an archeologist to brainstorm on ways to “deter inadvertent human intrusion” into the site.

Michael Brill, the architect on the team, wrote a paper about the experience, entitled “An Architecture of Peril.” He described the different messages the landmarks were intended to convey to future generations. Among them: “This is not a place of honor … no highly esteemed deed is commemorated here … nothing is valued here. What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us.” He wrote that he and his fellow experts decided that whatever was built, its “craftsmanship should be of low quality,” and even though the “enormous size of the enterprise and of the structure demonstrates an enormous investment of labor … this coupling of great effort with material of low value suggests place is important but dishonored.”

Some team members suggested a simple sign that read: “Danger: Poisonous Radioactive Waste Buried Here. Do Not Dig Until A.D. 12,000.” This message would be repeated in every major language spoken today. The stone material into which these messages were inscribed would have a lot of extra room to accommodate new languages as they arose. The words would be accompanied by bas-reliefs of a screaming face and a sick face. Others thought it would be unlikely that any language would survive that long and came up with a wordless comic strip that showed people running away from the bad place.

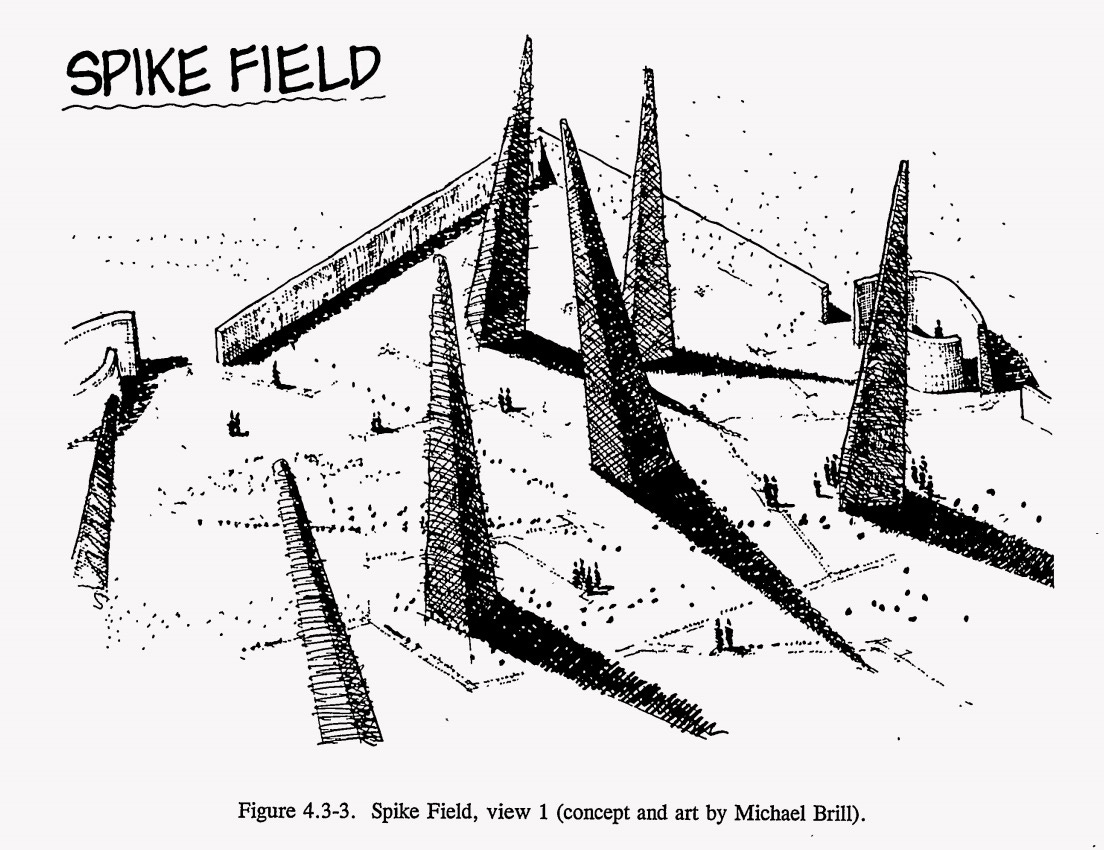

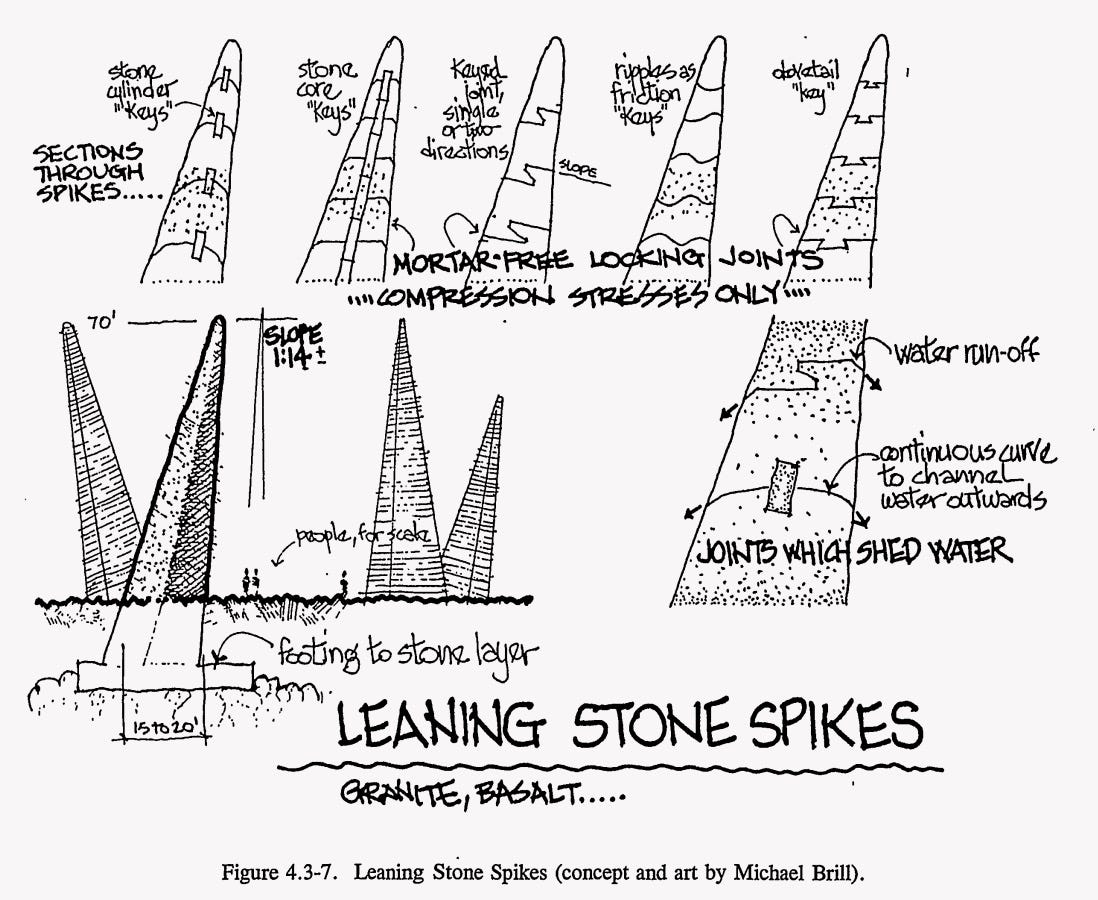

The experts also offered suggestions for structural elements designed to discourage anyone from digging around the site. “The Forbidding Blocks” option consists of a field of giant boulders spaced too tightly to walk between. “Leaning Stone Spikes” (above) would feature 80-foot-tall black rock obelisks erupting from the ground at irregular angles. “Menacing Earthworks” would erect a bunch of lightning-bolt shaped formations radiating from a central point. “Black Hole” would create a big round patch with cracks in it, suggesting parched, unusable land.” According to Brill, these “test designs” were supposed to convey the idea of “wounding of the body through dangerous emanations; keeping something buried that must not escape; and dead, poisoned, destroyed land.”

The sketches of the test designs are eerie, but they also exhibit an undeniable allure. They’re works of art, and therefore tempting traps for the curious. I don’t think any of them are as scary as the Forbidden Zone scarecrows from Planet of the Apes. Imagine encountering these alarming figures while loudspeakers blasted Jerry Goldsmith’s score. That would scare me away!

In 2002, the Desert Space Foundation held a competition for new ideas to mark another proposed nuclear waste repository in Yucca Mountain, Nevada. Again, most of the new designs seem more like lures than repellants. “Blatant and permanent markers will increase, not reduce the probability of inadvertent intrusion,” wrote Martin Pasqualetti, a professor of geography, in his paper, “Landscape Permanence and Nuclear Warnings.”

In light of this, perhaps one of the 1991 team’s rejected suggestions should be reconsidered: simply leave a small portion of the radioactive material above ground, so that anyone who wanders near it dies on the spot. What better deterrent than a pile of grotesquely blistered corpses?

There are also the intriguing ideas of genetically engineering a breed of cats whose fur changes color when exposed to radiation and establishing an “Atomic Priesthood” modeled after the Catholic Church’s success at safely maintaining its core messages for 2,000 years. “Imagine stories, objects, costumes, and rituals, all being used to convey the danger and power of nuclear sites and the taboo of digging up the radioactive material buried there,” writes Scott Beauchamp in his 2015 article for The Atlantic, “How to Send a Message 1,000 Years to the Future.”

Let’s see if readers of The Magnet, who are no doubt among the smartest, most creative people on earth, can come up with even better ideas for keeping people away from nuclear waste repositories. I asked my friend Josh Glenn, consulting semiotician and editor of the insightful websites HILOBROW and SEMIOVOX, for suggestions on how to think about the problem, and here’s what he told me:

In order to help future-proof a brand's visual identity, I normally recommend conducting a "diachronic" analysis of how the meaning of visual cues — from colors, shapes, type treatment, and use of white space to symbols, facial expressions, body language, etc, etc. — has evolved over time within a particular product/service category and/or cultural space. In other words, you can't predict the future without studying the past. So I'd look at how symbols of danger, like the skull and crossbones, have evolved over time and try to understand the trajectory of that evolution. For example, do we find a shift over time from "cool" to "hot" colors, or from naturalistic to cartoonish design/illustration, or from an authoritative to a peer-to-peer tonality, say? Or has there been more of a see-sawing back and forth between two such binary opposites — and if so, in which direction are we headed next?

With Josh's framing in mind, I invite you to add your ideas in the comments.

*This essay was modified from a chapter of my 2005 book, World’s Worst.

Just spreading a message for 10,000 years is hard enough, but you also need people to genuinely believe it for that long. Leaving some of the material above ground seems like the only way to give people a meaningful and believeable message, even if there are other ways to technically convey the same concept.